|

Singer’s Breathing and Breath Support Written for Walton Voices by Zoran Milosevic [email protected] 01932 246 635 Choir rehearsals and singing lessons will often start with a breathing exercise, usually a variation of “inhale for 5, hold for 5, exhale for 15 seconds”. It appears to be a quite simple and straight forward drill, except … that it is not! Each of the three steps have their peculiarities that are not intuitive. Taking a Breath Let us start with breathing in. We breath subconsciously, but at any level higher than casual or bathroom singing, breathing should be done in a particular manner. Breathing is accomplished by altering the size of the chest cavity, sucking the air in when the cavity is expanded (creating vacuum inside the lungs), and expelling it when the cavity is contracted. These actions are initiated automatically by nerve signals that the brain sends to the relevant muscles, be it the inspiratory (inhaling) or the expiratory (exhaling) muscles. We can change the size of the chest cavity by following muscle actions:

Note that in normal breathing inhalation occurs via an active (albeit subconscious) contraction of muscles – such as the diaphragm – whereas exhalation tends to be passive, initiated by relaxation of the inspiratory muscles - unless we purposefully force it (e.g. when singing or blowing a candle). When the inspiratory muscles, such as rib’s intercostals and the diaphragm, are relaxed for exhaling, the elastic recoil of the lung tissue allows the lungs to return to their original size and expel the air. But when we sing, our breathing is not “normal”, it is forced: we force our lungs to inhale in a certain way, we hold the breath briefly after inhalation to prepare the body for the “breath support”, and we force the expiration to follow the music’s tempo and to have a defined, desired breath energy, which is going to vary depending on what we sing - forte or piano, high or low notes. Therefore, during vocalisation, both the inhalation and the exhalation muscles are active. When we take the air into the lungs and are about to breath out, the tendency of air to rush out of the lungs is so great that, in order to counterbalance this force, to hold the breath for a moment, and to produce a controlled flow of air suitable for singing, the inspiratory forces must actively counterbalance the passive recoil forces. To accomplish this, the internal intercostal muscles and diaphragm remain active and recoil slowly to their resting state in order to control the outflow of air. Singers take breath predominantly by using the abdominal breathing mechanism, whereby the breath is taken low in the lungs. The inhale is quiet, through the nose, and is deep, but without overcrowding the lungs. In singer’s breathing the chest does not move perceptibly; it retains its high, slightly protruded position. Most of the expansion and movement on inhalation are observed in the middle abdominal region. Abdominal breathing enables the singer to subsequently push the air out by using the abdominal muscles. That is a much more precise and controlled mechanism for exhaling and singing than pushing the air by contracting the rib’s intercostal muscles. Breath intake must be deep; this is essential as it places the larynx in optimal position for singing (lowering it, and also slightly widening the throat). A deep breath also forces the two vocal folds to move wide apart, so that the whole mass of the two vocalis muscles moves out, away from each other, and is subsequently broth together in a manner that the whole mass of vocal fold vibrates, creating a rich sound. A shallow breath does not result in wide opening of the vocal fold on inhalation, and they cannot be brought together in a way that enables “good vibrations”. It is true that singers must occasionally take a very short breath between phrases; trained singers can do that and still keep the throat fully open as they learned to assume the “noble” throat position even without taking a breath. There are two basic kinds of abdominal breathing.

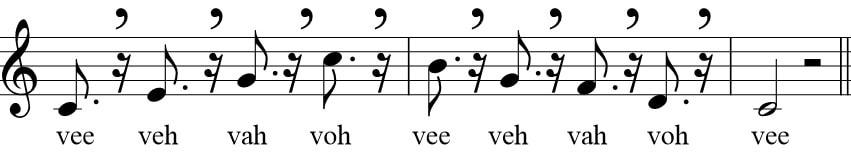

Belly stick-out is the simpler method, often practiced in choral singing and some older schools of solo singing (e.g. German). It involves relaxing the lower abdominal muscles, whereby the lower belly descends, sticks out and pulls the internal organs down and the diaphragm with it. While working reasonably well, this breathing technique is not part of the classical singing of today for several reasons: (a) the bely dropping down also pulls the chest down and causes it to somewhat collapse, thus distorting the optimal position of the chest/larynx assumed at inhalation; (b) The abdomen is relaxed on inhalation with this method, so the singer needs to perform an active muscle action to re-tighten the abdomen and prepare it for the subsequent holding of the breath and supporting the breath on exhalation; (c) it restricts the upward movement of the diaphragm during phonation and limits the breath support for the upper voice. Although the belly stick-out method may be considered adequate in choral singing, I would encourage mastering the abdominal inhalation where the lower abdomen remains tucked in, and expansion is observed mainly in the middle abdominal region, then at the sides and perhaps a little in the back. Holding the Breath (Suspension) Breath suspension does not occur in natural breathing where exhalation immediately follows inhalation. In singing, however, the breath is held for a moment just as inhale is completed. The purpose of this suspension is to prepare the breath support mechanism for phonation (the making of the sound) that follows. The key to good suspension is to keep the throat open while holding the breath, and keeping the inhaling muscles engaged, the whole body thus staying in a position as if still inhaling. The open throat ensures that the larynx closes only at the onset of the tone; it does so by a skilful and measured closure of the vocal folds, synchronised with a timely and measured abdominal exhaling action. Such tone onset is called the “balanced attack”. The opposite would be to close the larynx while holding the breath, relaxing the inhaling muscles and letting the lung tissue elasticity build pressure in the lungs before the sound is made. The subsequent tone onset would in that case be through a release of air over vocal folds, caused by sudden opening of the larynx – the air rushing out due to lung pressure build-up and its sudden release. The resulting tone onset would be a “hard attack”, and is not part of classical singing technique. The singer wants to effectively control the breath pressure and the air flow, not to let the lung pressure suddenly drop and the air rush out uncontrollably. Exhaling Exhaling is seen as continuation of holding the breath in that the abdominal inhaling muscles retain their inhaling position and tension. Actually, all singing should feel as if you sing on the inhaling breath – the inhaling muscles are still engaged, and the belly is still expanded around the middle. The throat of course remains open, in the same position that it assumed during the phase of holding the breath. Most importantly, the larynx does not move up as you start exhaling, and it must not move when you stop. This larynx stability should be practiced - keeping the larynx in a stable position at the tone onset and during singing is an essential skill for every classical singer. In normal breathing there is a relatively long “recovery” phase: at the end of each breath there is a moment when all the muscles associated with breathing relax. In singing, this moment is shortened, but must not be omitted, as inexperienced singers often do, causing fatigue and accumulated tension. Support (appoggio) As soon you take a breath, you will feel an urge (automatically created) for the expiration muscles to expel the air. “Support” in singing refers to the muscular tension that maintains a desired pressure inside the lungs and a controlled air flow during singing, essentially by maintaining for as long as possible the posture assumed at inhalation, retaining the air in the lungs and opposing the action of the exhalation muscles to expel the air quickly. Some schools of singing actively teach appoggio, and the other do not teach it explicitly, but guide the inhalation process and tone onset so that the support happens spontaneously. For a choral singer, as long as breathing is abdominal (“diaphragmatic”) and the lungs are not overcrowded, some appoggio will be appropriately applied as soon as the singer has learned the balanced tone onset and aims for sustained notes with consistent sound quality. Exercises Breathing 1 – In, hold, out, with open throat Inhale low in your abdomen for 5, hold for 5, exhale quietly for 5 seconds. Then repat it, holding for 6 seconds each, and continue increasing the count for as long as you are comfortable, aiming for 10 seconds each. Make sure the larynx remains open and does not move throughout this exercise. Breathing 2 - Quick exhales On a single breath exhale as quickly and vigorously as you can on “hu-hu-hu” for 5 seconds (about 15 quick exhales), then continue to do the same through the nose, and finish with a long “hmmm”. Inhale and repeat three more times. (Note how hard is this to do with overcrowded lungs). This exercise is borrowed from the excellent set of warmup drills by Canadian baritone Lucas Meachem (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VyMb-hNYxh4) Breathing 3 – Lip Trill This is also an exercise for building breath support, because there is no lip trill without support. Start at a comfortable pitch and do the trill - “bhrrrrr” on a series mi-re-do-re-mi-re-do-re-mi-re-do three times. If the voice sounds well, continue upwards. If the voice does not feel quite warmed up, go down in pitch. Note that a lip trill can be overly supported and under-supported. You want to be in between, lips relaxed, air flow stream steady and not too forced. The sound should “go out”, not be kept back in the throat. Continue with octave arpeggios: do-mi-sol-do-sol-mi-do three times, keeping the sound in the same space throughout the arpeggio. Make sure that you go over the top note without accenting it and without making it louder. The destination in the phrase is the note you started at, not the top note. Breathing 4 - Breath Support This exercise is borrowed from our own guest conductor Christopher Goldsack’s fabulous set of exercises created for his Promenade Choir (http://www.promenade.org.uk/warmups.html). Support each note to the end of its duration. Let the release of support initiate the next breath. Let the new support come elastically from the previous. The “v” consonant will engage your abdominal muscles. The exercise is shown for high female voice, it starts at C and goes higher. For other voices please adapt accordingly.

The above four exercises are likely to make part of your daily regimen that I am going to propose later, once we have covered other essential topics of good voice production. In the next post I will discuss the ever so important topic of tone onset.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

It's good to share!Got something you'd like to share with us all? Perhaps some interesting research, an event or experience or some other art, media or enterprise that you'd like to contribute. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed