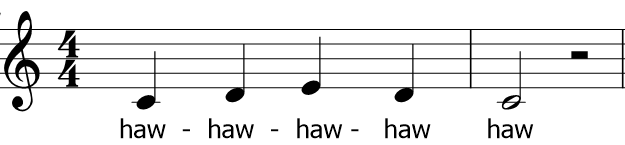

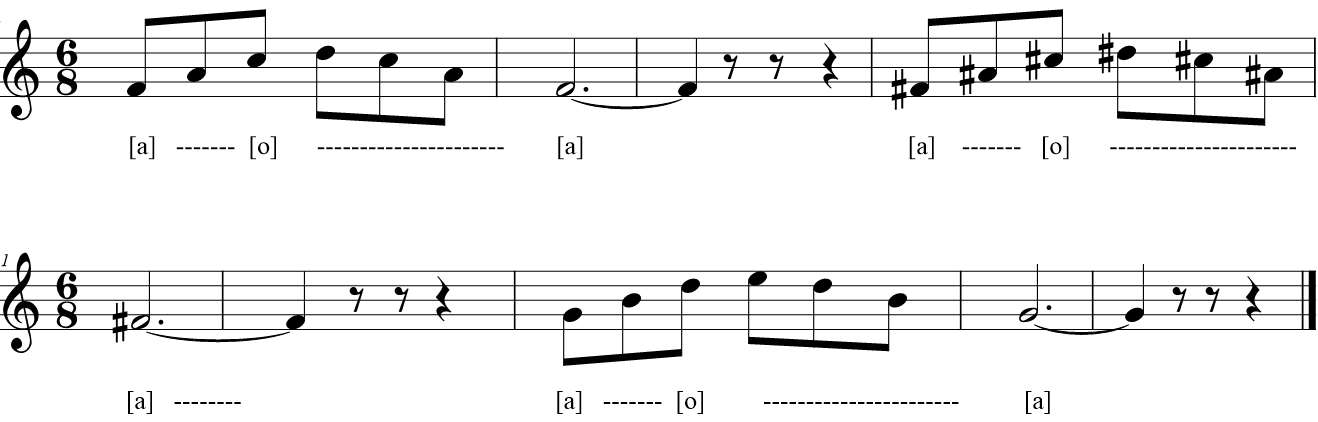

“Head” voice is a term used to describe the type of voice that creates a ringing sensation in singer’s head, as opposed to the “chest” voice, which causes the vibrations to be felt mainly in the chest. The difference results from the alteration in the shape and the thickness of the vocal folds, specific to these two voices. Head voice should not be confused with falsetto, the highest register of the male voice. Falsetto is not used in classical singing; it may be used in humorous imitation of the female voice, and in certain range-extension drills. Head voice occurs over a series of pitches where the vocal folds are stretched and thin. This thinning is a result of the increased activity of the cricothyroid (CT) muscle (vocal fold lengthener) and decreased activity of the thyroarytenoid (TA), or vocalis muscle (vocal fold tightener), which is the muscular body of the vocal folds. Head voice is sometimes referred to as the “lighter mechanism” of the voice because there is less vocal fold mass involved in its production. Head voice is usually described as bright and ringing. The two muscle groups described above are used by classical singers to vary the pitch of the sound they produce. The singer can tighten/shorten the TA muscle, which raises the pitch; he can also stretch/thin the vocal folds by using the CT muscle, which does so by tilting the thyroid cartilage (the Adam’s apple). Trained singers use both these mechanisms, as well as the mix of the two, in order to access and acoustically equalise and smoothen their entire vocal range. For various reasons, including social habits, the male voice has a chest-dominant quality to its speaking voice, while the female voice has a head-dominant quality. It stands to reason that over the years, the dominant register of the two voices will be the one that is most developed. As a result, men seldom have a well-developed head voice without having specifically trained it. The consequence is a limited vocal range and no access to high notes. While the chest voice is resonant, warm and masculine, it can only take the singer up to his 1st passaggio, an important pivotal point in every voice where the switch from “chest” to “head” must begin. Baritones can find it hard to sing above C# or D, and tenors above E or F by using the chest voice only. If they continue to ascend in the chest mode beyond the 1st passaggio they will strain the voice, forcibly raise the larynx and turn the voice into a yell and eventually break into the comedic falsetto. Note that raising the larynx is an alternative (the third) pitch changing mechanism, and undesirable in elite classical singing. It is worth noting that many female singers, even operatic professionals, can sing their entire range in the head voice. However, while not needing the chest voice that much, sopranos would benefit from having a well-developed chest voice. While the “chest” may not be used directly by a female singer, having it gives depth and fullness to her head voice. In summary, female singers can live without the chest voice, while male singers must develop the head voice and use it in addition to their obligatory chest voice. When training male singers, the voice teacher must intervene to identify and develop the “unused” head register. Many young male singers attempt to sing classical repertoire using the only voice that they know, the chest voice. Their attempts result in a severely strained, uncontrolled, and spread sound as they ascend. Male singers must understand how to relax the TA muscle and activate the CT muscles of the larynx as they approach the pivotal point called the 1st passaggio, enabling the voice to “turn”. To some readers this change may be known as “covering” the voice. It is highly desirable that the head voice is demonstrated to the untrained singer, who may even be unaware of its existence. Many examples are available online. It does not take long to get the hang of the head voice, and it opens up a whole new world to a bass, baritone or tenor. There are several approaches to teaching the head voice, depending on how developed the voice is – existent but undeveloped, or the student has no access to it at all. Finding the Head Voice Without a vocal instructor, finding the head voice requires some vocal exploration. Here are a few ideas. · For those males who have no access to it the first step is usually to learn to speak in head voice, imitating storytelling speech practiced by storytellers that use head voice for young characters in the story. · Yawn sighs are the next step between speaking in head voice and singing in it: slur from the very top of the vocal range to the bottom and keep the voice light and airy. · Next, try an exaggerated, voiced sigh. Slide as slowly as possible, noting all the variations in the voice. Men have a natural break between their falsetto (highest notes) and head voice (next highest). The next step is to sing in head voice. · Start with a yawn sigh and stop somewhere in the top of the voice and hold the note. If volume is added, the singer should suddenly find himself singing in the head voice. At first the brighter vocal sound may not be favourite to a male singer, but he will soon realise that it leads to greater vocal freedom as the singer learn to mix in the warmer sound of chest voice. · Sing “miaouw” in comfortable vocal range. The combination of vowels with encourage a high larynx position; while a high larynx is not a goal itself in classical singing, it facilitates finding the head voice.  · · Now sing “haw” with the larynx positioned lower. Having found the head voice with the larynx raised, try singing it without raising the larynx, for which the “haw” combination is well suited. Go up in pitch as comfortable. Note: while singing with a low larynx and relaxed throat is a major training goal for every voice, it will take many years of vocal training to achieve that throughout the whole range. Baritones will generally not be able to sing above D (tenors above F) with a low larynx, and the upper limit of the relaxed classically produced sound would be around the middle C for baritones (D# for tenors) until well into their careers, when baritones will extend the relaxed, classically produced sound to E and above, and tenors to G and above. By completing and repeating the above exercises, a male singer should have discovered the head voice and hopefully realised that high pitches are more easily accessed by its use. The next section concerns further development of the head voice and contains a slightly more advanced material. Closing the Vowels Eventually, the singer should be taught that the head voice will occur when he learns to close and darken the vowels as he approaches the breaking point of the 1st passaggio. As a result of this “closing”, vowels will migrate towards their neighbouring vowels: [a] will migrate towards [o], [o] towards [u], etc. Certain vowels are already calling on the activation and coordination of the cricothyroid (CT) muscles, guaranteeing a balanced mix of adjustments that is necessary as singer ascends, as is the case in [a] to [o] transition used in the next exercise. The singer begins on an open [a] vowel. On the third note of the exercise, he changes to the [o] vowel and then cadences on the last note on [a]. The singer should feel the voice transitioning from chest to head as he closes the [a] vowel changing to [o].

Strengthening the Head Voice Many exercises that start on the top and move down develops the head voice. Using the ‘w’ also helps lengthen the vocal cords before starting singing, setting the singer up for a cleaner sound. One much used exercise combines the two: · Sing ‘we-e-e-ah’ on a simple arpeggio 1-5-3-1. That would be C-G-E-C in a C-major scale. Make sure to connect each note. Sing up the scale as high as possible without hurting the voice. · Once the simple arpeggio is mastered, the singer may try a 5-note scale beginning with ‘w,’ as in ‘we-e-e-e-e,’ on 5-4-3-2-1 or G-F-E-D-C in a C-major scale. The key is to really close the lips when producing the ‘wuh’ sound. Another exercise involves the use of falsetto. · The singer starts singing [i] or [u] on a mid-range note, say F for a baritone or G# for a tenor, in piano falsetto. He then crescendos to the full voice and back to falsetto. The full voice produced by transitioning from falsetto will be the head voice. · Taking a new breath, the singer then sings on the same pitch in the same full voice. He then progresses by half steps over a period of weeks or months through to the upper limit of his head voice, which can be around E for baritones and G for tenors. Getting to this pivotal point called the 2nd passaggio is a major event for a male singer. The next steps in his singing career are learning how to produce a uniform sound when approaching the 2nd passaggio and then singing above it. These two developments require major additions to the singing technique and involve year of practice to master.

2 Comments

Tim A

27/3/2023 09:36:59 pm

Great article thanks! Trying to find my way around my voice and this was very clear!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

It's good to share!Got something you'd like to share with us all? Perhaps some interesting research, an event or experience or some other art, media or enterprise that you'd like to contribute. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed